1986 The Chernobyl Plume

At 01:23 local time on 26th April 1986, following botched tests at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in the Ukraine, there was a very dramatic rise in core temperatures. This caused an explosive generation of steam and rapid chemical reactions which dislodged the enormous 1000 tonne cover plate and spewed debris all over the site.

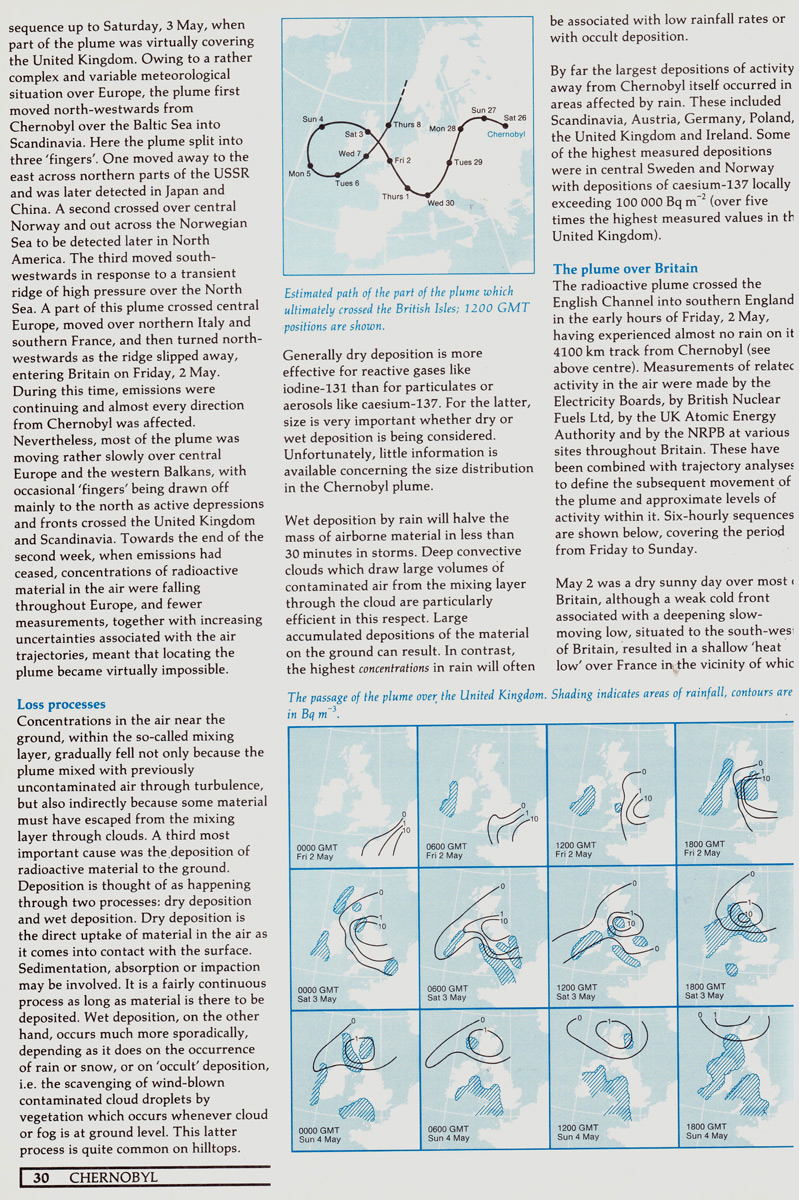

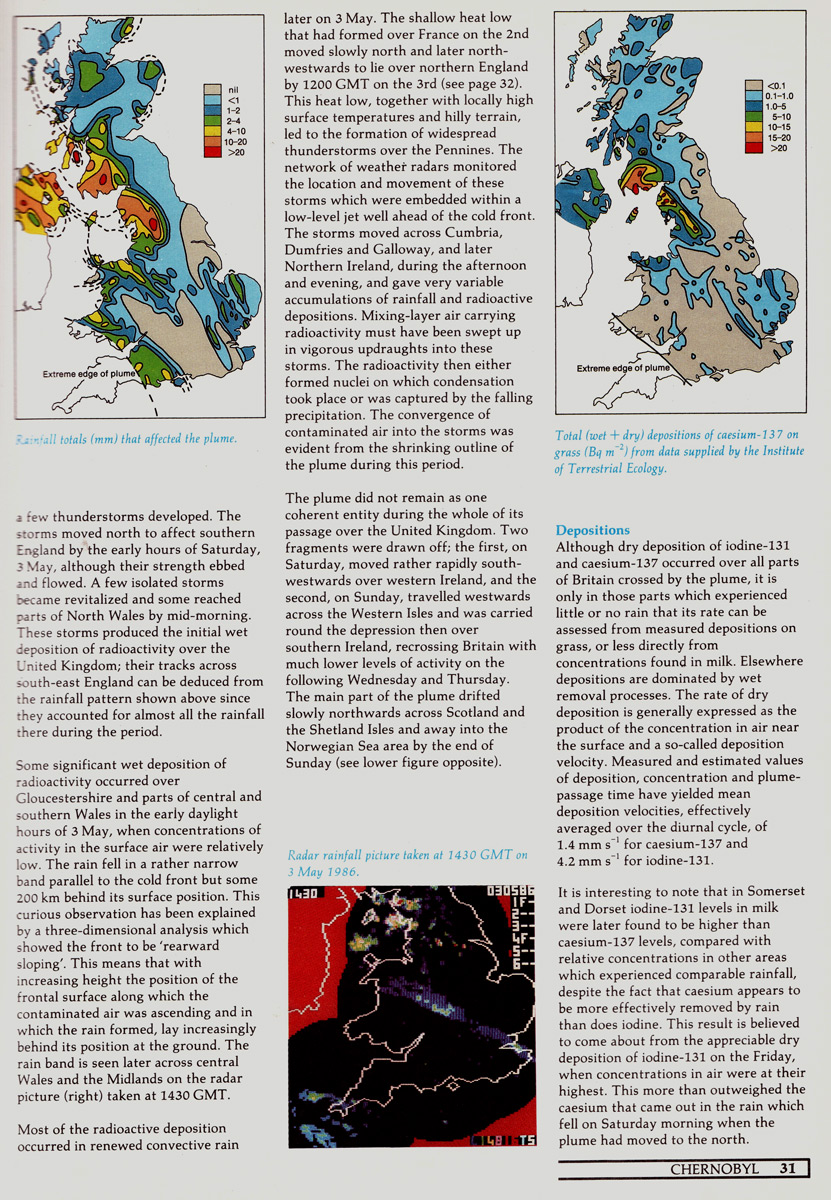

And so it began. Two of the products released in quantity, which were most important from a health point of view were iodine-131 and caesium-137. It was not until one week later, Saturday May 3rd, before the plume reached Ireland. At this stage the concentrations of radioactive material in the air had lessened considerably. Nevertheless by far the greatest depositions of activity away from Chernobyl itself occured in areas affected by rain. These included Scanadanvia, Austria, Germany, Poland, The U.K. and Ireland.

Wet deposition of radioactive material was a problem over Ireland for a few days in early May. In particular deposition of caesium-137. The rain had the effect of bringing down the radioactive particles to ground. Kilkenny did not escape the plume. Had it not rained during the times the plume passed overhead, the deposition would have been much less. Here then are the daily rainfall figures from Kilkenny Met Station for early May 1986:

|

Kilkennny Meteorological Station : |

Date | Rainfall (mm) |

| May 1st | 0.0 | |

| May 2nd | 0.5 | |

| May 3rd | 5.1 | |

| May 4th | 7.9 | |

| May 5th | 8.9 | |

| May 6th | 7.1 | |

| May 7th | 3.1 | |

| May 8th | 0.3 |

The day of note was May 3rd when 5.1mm fell. Even though more rain fell on the following Sunday, at this stage the plume had moved further further north and then west away from Ireland and concentrations/depositions were a lot less. On Wednesday May 7th a weakened version of the same plume managed to pass just to the south of Ireland and 3.1mm of rain fell on this date.

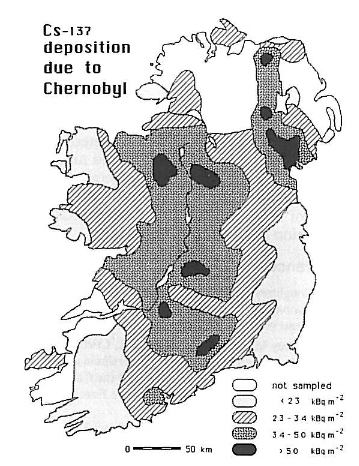

McCaulay & Moran (1989) produced this chart showing the estimated depositions in Ireland of caesium-137 from Chernobyl :

As always, rainfall totals during this period were greater in more upland areas. An additional problem with upland areas (such as the Comeragh and Blackstairs Mountains) is the peaty soils. As Ciara McMahon from the EPA explained to the journal.ie in this article, "caesium binds to clay in lowland areas (a process that essentially takes it out of the environment) but not to peaty soils".

The journal.ie article explained how sheep bore the brunt of the radioactive fallout. "Heather and mosses also take it up more effectively than other plants. Upland sheep tend to eat those, so the combination of peat and the vegetation meant we were able to detect it in sheep for longer."

There are several accounts of Irish exports of contaminated foodstuffs (powdered milk, butter, lamb) being rejected by some of the poorest countries of the world back in the late 1980s.

There is quite a difference, then and now, comparing how Kilkenny fares in two radioactivity reports:

2) EPA Radioactivity Report 2015

In the first report, the highest levels of radiocaesium in lamb were found in samples from the Kilkenny region (the highest level being 1155 Bq/kg). Levels in beef were a lot less but again the highest levels were in the Kilkenny/Waterford region. Also the highest radioiodine level in milk samples was detected on May 5th in Kilkenny when 441 becquerels per litre were recorded. By May 13th this had fallen to 30 bq/l as radioiodine breaks down rapidly (Iodine-131 has a half life of only 8 days compared to 31 years for Caesium-137). So quite clearly the plume had made an impact on County Kilkenny.

Fast forward now to the milk samples taken in 2012/2013 for the EPA report 2015. Neither caesium-137 or iodine-131 were detected in any samples during the reporting period. I cannot find any specific mention of tests on lamb in the EPA reports since the surveillance programme of 1999/2000. In that report the highest level found in lamb was only 17.8 Bq/kg, a welcome large drop from the 1000+ sample found immediately after the disaster in 1986. Anything below a figure of 600 Bq/kg is considered a "safe" level.

So 30 years on it is important to put the matter in context. The radioactive particles can only be detected in the soil using sensitive equipment. Continued monitoring has shown that levels detected in foodstuffs is considerably less than it was 30 years ago. The journal article quite correctly points out that the Irish public is at greater risk from a homegrown threat rather than the likes of Chernobyl: that being radon gas.

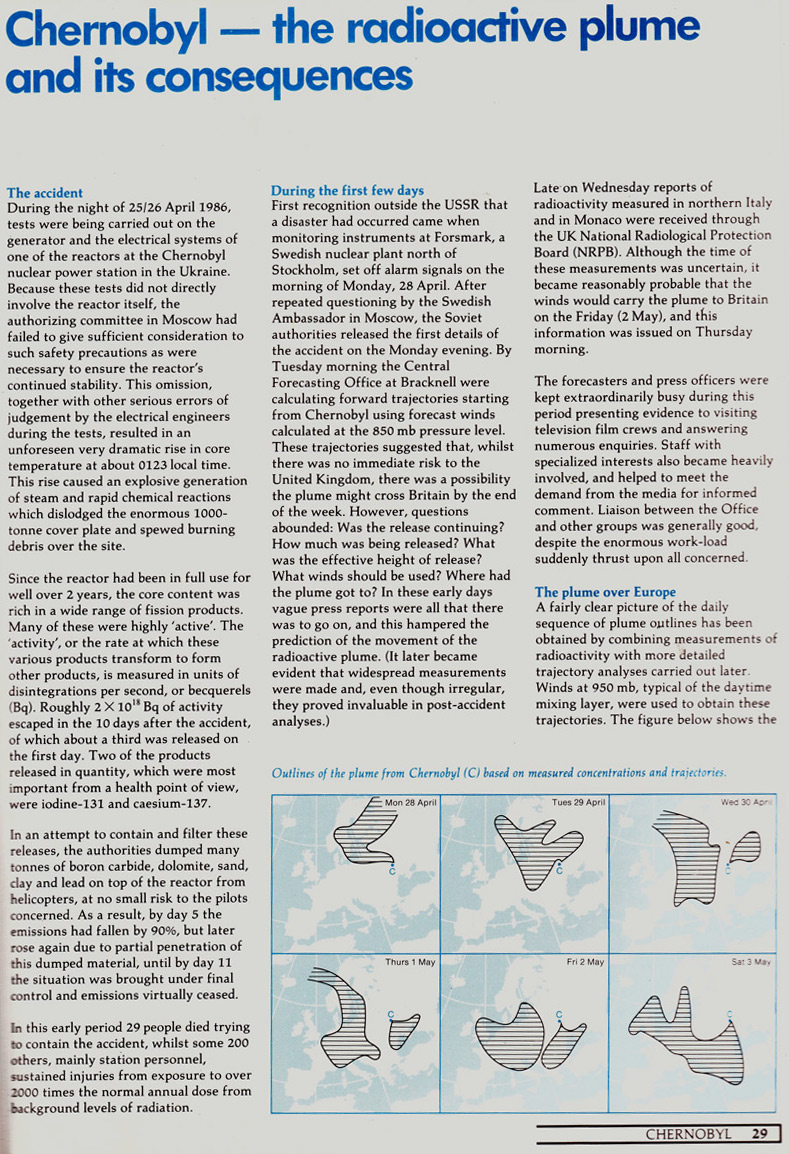

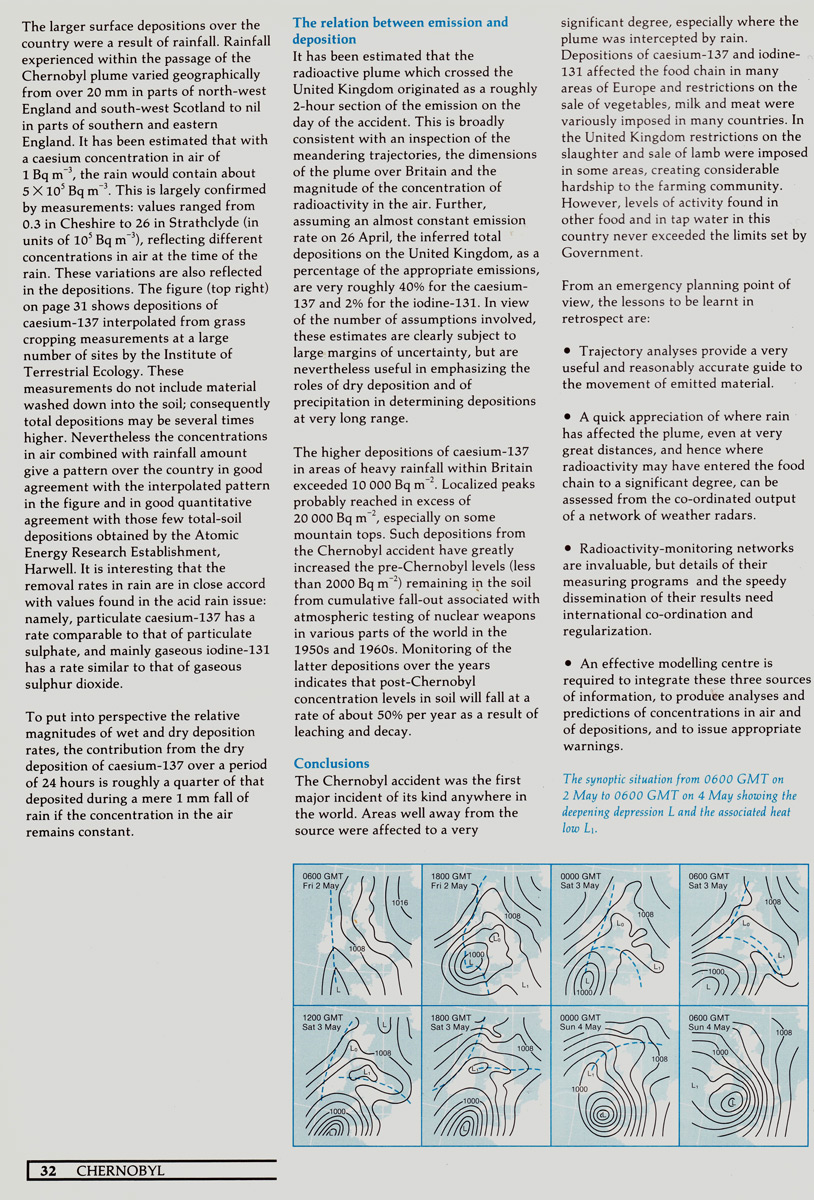

The following is a detailed account of the plume produced by the UK Met Office in their Annual Report of 1986 :

Of course the contamination levels in Ireland were far, far less than that in the immediate vicinity of the power plant. This map below (By CIA Factbook, http://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/belarus.html) from 1996 shows significant areas in Belarus and Ukraine that are either controlled or closed zones. It is quite remarkable that the nearby city of Kiev managed to escape the worst of the plume, such were the vagaries of the wind direction at the end of April 1986.

Note : 1 Curie per square Km = 37,000 Bq per square metre.

The lowest coloured zone above is at that level. By contrast the darkest coloured zone in the Irish Mcaulay and Moran map shown above was only 5,000 Bq per square metre.

Ireland has gotten away lightly compared to this long lasting legacy in the Ukraine and Belarus.

2017 Close Encounter with a Hurricane

2017 Close Encounter with a Hurricane